How to track license plate cameras tracking you

I never suspected the meter maid.

Sure, we take constant, unblinking (if mostly uninterested) surveillance for granted these days, but I blame the usual suspects: the FBI, ATM cameras and those not-so-discreet bubbles above cashiers at the grocery store.

Then I read an ACLU report on automatic license plate readers, an emerging class of high-speed cameras that can scan and identify thousands (millions?) of passing cars per hour. The idea is that a computer can run photographed plates instantly through a carjacking database and alert police if a stolen vehicle drives by, but the ACLU found that many police agencies were keeping all the non-hits as well, building massive databases of when and where people were driving.

I'm Andrew McGill, a product builder who turns delightful ideas into real things.

I used to make stuff at The Atlantic and POLITICO. Now I build things with people like you.

After looking through the ACLU’s online map of records-request responses, I realized one unexpected Pittsburgh agency was very interested in the technology: Our municipal parking authority.

Yep, the folks who ticket you for pulling too close to the hydrant.

Apparently, the PPA was using the cameras to find folks who had amassed obscenely high fines, stopping as they passed by on the street and booting their cars. Through Pennsylvania’s open records laws, I obtained from the authority a database of every car scanned in August 2013 by the PPA’s two boot trucks, who toodle throughout Pittsburgh most weekdays.

Turns out those two trucks are really freakin’ efficient, scooping up between 150,000-200,000 license plates every month. And sure enough, they weren’t deleting the licenses plates that DIDN’T have fines.

Filter that database by a certain plate number, voila: You can track a car’s location through the city. For example, here’s a screenshot of all the locations license plate HYN8398 had been scanned. (That plate belongs to a shuttle van, so it chills downtown a lot.)

Kind of freaky, huh?

I ended up writing this story about the practice, highlighting a lady from the city’s Beechview neighborhood who had unwittingly been photographed all around town. The Parking Authority eventually responded, promising to clear out its database daily.

How I did it

This data came on two USB drives in a collection of wonky, 40,000-entry HTML tables. Concatenating those together using Notepad++, I opened the combined file in Excel and converted it so a CSV (it was only about 150,000 lines, so not a problem for Excel 2007 and up). Dumped that file in Access.

I quickly figured out that some of the reads were duplicates — the camera would have two separate images at the same location and the same time. To get rid of those, I used Access’s “find duplicates” wizard along with this method, using the timestamp (which was unique) as my primary key.

The database would also use a regular expressions-like syntax for a license plate’s number if the camera didn’t get a full read. I want those included when querying for the count of unique plates, so I made sure to include a NOT LIKE “*[[]*” clause in my SQL.

That gave me a reasonably clean list of unique moments a license plate had been photographed. But now I wanted a good example for my story — a person who had been photographed multiple times at disparate locations in Pittsburgh.

Standard deviation to the rescue. Calculating the standard deviation between any given plate’s various scanned latitudes and longitudes let me pick out vehicles that had been photographed multiple times and in different places.

At the same time, I had to actually find these cars, too. So I looked within the set for plate numbers that also had modest clusters of records very close together in a residential neighborhoods, wagering that might be where its owner lived. That’s how I found Donna Scuilli: Here’s what a portion of her records looked like mapped out.

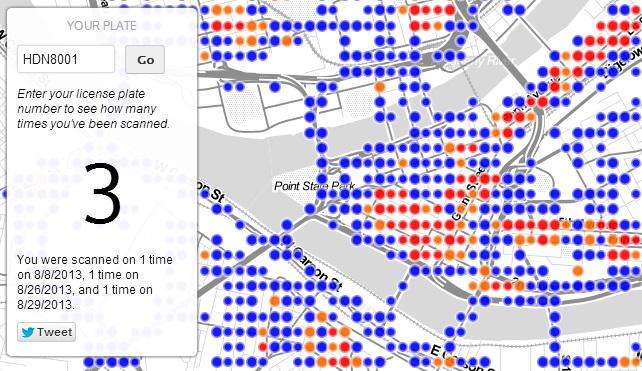

I also built uploaded the database to a mySQL server and built a simple web tool empowering people to search for their own license plates. It wouldn’t show them where they had been scanned — what if a guy put in his ex-wife’s plate number and found her new house? — but it would show them how many times they’d been photographed and when.

Take me: I was scanned 3 times (all while parked on my street).

I’ve uploaded the cleaned dataset (no duplicates but still ambiguous plate numbers) to Github.

I’d love to chat. Drop me a line.